Wildlife and conflict

The unintended consequences of environmental protection policies

This study aims to shed light on the link between armed conflicts and biodiversity loss.

Guy Pincus

PhD Student in Economics

London Business School

This study aims to shed light on the link between armed conflicts and biodiversity loss.

Guy Pincus

PhD Student in Economics

London Business School

Close video

Close video

The problem of wildlife trade is similar to the textbook public-good problem, whereas myopic economic agents over-exploit resources to a level of extinction. In the case of wildlife, this problem is even more complex due to the limited enforcement capacity in remote areas.

Identifying the role of armed groups in wildlife trade, and understanding their financing mechanism, is essential in order to fight against terrorism, promote social stability, and design effective environmental protection policies.

The world stock of megafauna and wildlife is essential for a healthy and stable ecosystem and constitutes one of the most important public goods. Scientific studies have shown that biodiversity loss can have long-lasting humanitarian consequences for crop yield, the spread of disease and climatic shocks.

As an example, Elephant populations fell from about 1,300,000 in 1979 to around 400,000 today. Despite the international ban on ivory trade enacted in 1989 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, estimations are that in 2010-2012 around 34,000 African elephants were poached annually. Regardless of banning international trade in rhino horn in 1975, today, the total population is estimated at 26,272, whereas in 1970, their population was around 70,000.

Map: Africa tropical forests

Environmental damage caused by resource extraction is a fundamental concern. Many African states are home to a vast amount of natural capital – with 8 out of 10 in the list of the most biodiverse countries. Tanzania, South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo are on top of the list. This provides a fruitful ground for armed groups to extract and exploit natural resources in order to fund their political agenda.

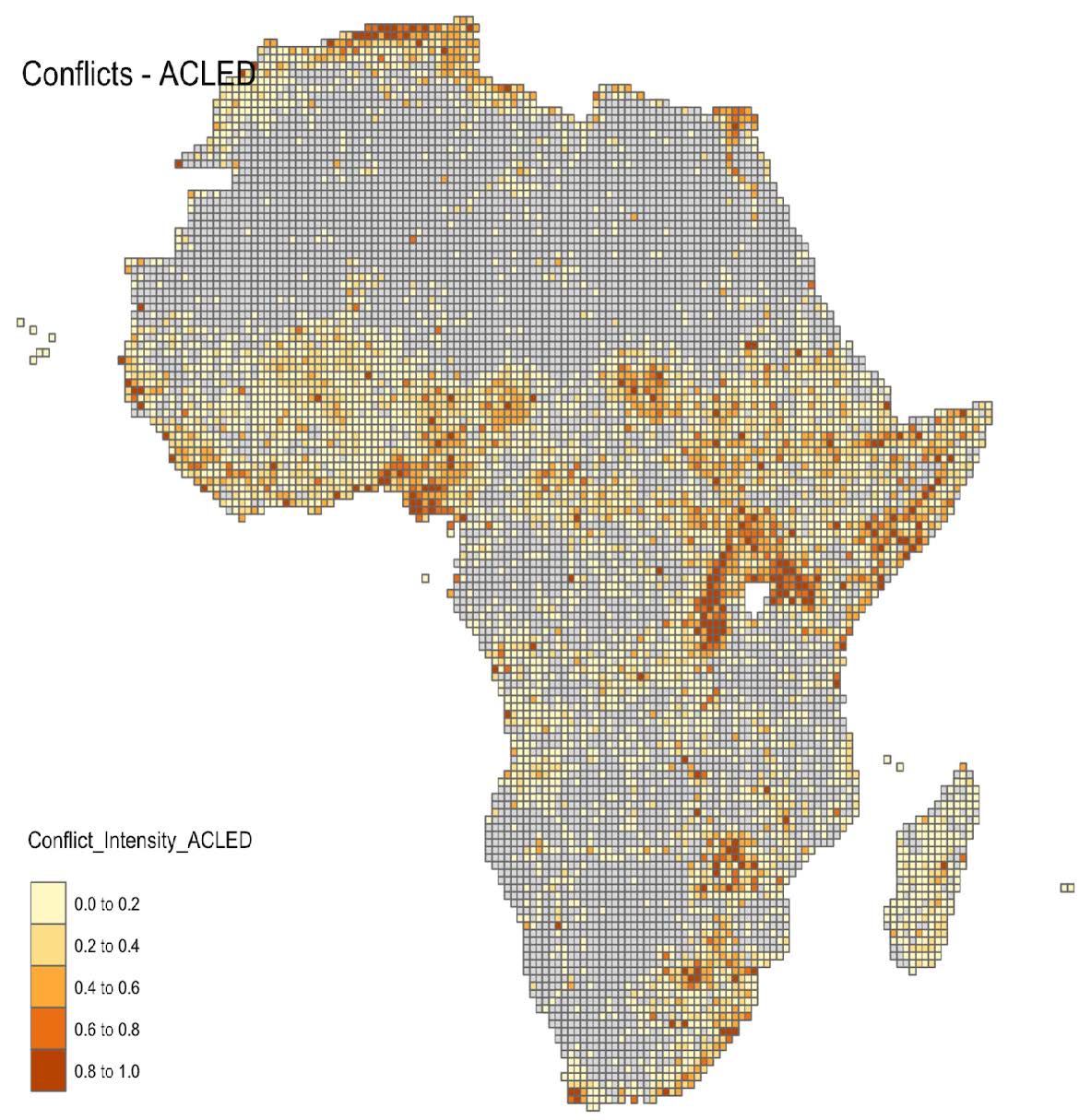

To identify the link between armed groups and wildlife trade, the researcher constructs a georeferenced grid combining data about conflicts and wildlife habitat areas for each species. The data uses either corresponding policy shocks or prices as a source of time-variation.

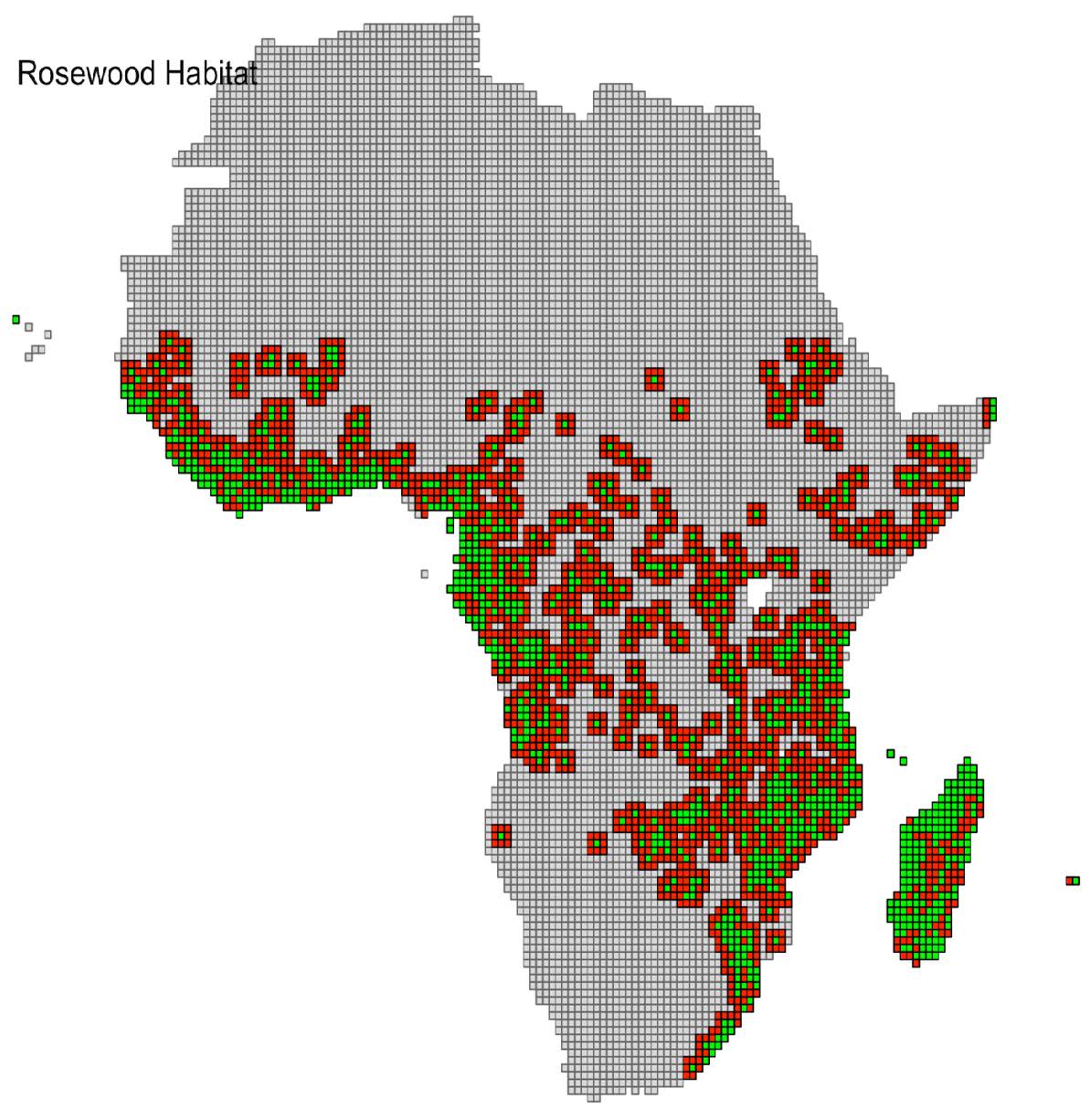

Looking closer at megafauna, this study also shows that similar patterns emerge in the case of expensive protected trees like African rosewood and ebony that suffer from high demand in China.

Elephant habitat distribution across Africa. Those areas are likely to experience armed conflicts and armed groups activity following an increase in the price of ivory.

Rosewood habitat distribution across Africa. Those areas are likely to experience armed conflicts and armed groups activity following an increase in the price of African tropical timber.

Spatial distribution and intensity map of conflicts across Africa. ÄCLED.

This study aims to improve our understanding of how armed groups and warlords finance their operation, identifying a major channel for biodiversity loss, and improve future conservation policy design.

Empirical contributions

Practical contributions

Theoretical contributions

Guy is a PhD Student in Economics at the London Business School. He holds BA (IDC) and MSc (UPF) in Economics.

Before joining London Business School, Guy worked in the financial sector (Brevan Howard and Calypso Technology). Later, as a researcher at the Aaron Institute for Economic Policy, Guy was responsible for the “Arab Society Project – Minorities in Israel as a Potential Growth Stimulator”.

Guy’s research agenda is strongly inclined toward empirical research,

mostly around policy matters. Specifically, Guy is primarily interested in economic policies related to politics, development, illegal markets, culture and environmental issues.